The stories of the Ice Age National Scenic Trail and Ice Age Trail Alliance are a fascinating mix of vision, conservation, and passion, involving both famous Wisconsin politicians and thousands of private citizens.

Inspiration

Ray Zillmer

During the 1920s, extreme flooding of the Milwaukee River, coupled with increased recreation needs of the growing city of Milwaukee, focused attention on the Kettle Moraine, a scenic belt of glacial ridges in southeastern Wisconsin.

The Milwaukee Chapter of the Izaak Walton League purchased 800 acres around Moon Lake (now Mauthe Lake) in the Northern Kettle Moraine in 1926. Ten years later, the Kettle Moraine State Forest was established and volunteers began constructing its first hiking trails.

Among the leading proponents for the protection of the Kettle Moraine was Raymond Zillmer, a lawyer by profession and an avid walker, mountaineer and student of natural history.

He explored the wildlands of northern Minnesota, mountaineered in remote areas of the Canadian Rockies (Mt. Zillmer in the Cariboo Range was named in his honor) and followed the development of the Appalachian Trail. Zillmer was twice responsible for personally convincing two governors to increase land acquisition funding for the Kettle Moraine State Forest.

In the 1950s, Zillmer envisioned the Kettle Moraine State Forest forming the nucleus for a much larger linear park that would be used “by millions more people than use the more remote national parks.” He pictured extending the Kettle Moraine Glacial Hiking Trail along the terminal moraine of the most recent continental glaciation for several hundred miles.

He was certain the concept warranted national attention.

A National Park to Commemorate Continental Glaciation

In 1958, Zillmer founded the Ice Age Park & Trail Foundation (now the Ice Age Trail Alliance) to begin efforts to establish a national park in Wisconsin that would encompass this route. That same year, he wrote a letter to Daniel Tobin, Regional Director of the National Park Service.

Zillmer wrote: “I am intimately familiar with the moraines…of the existing Kettle Moraine State Forest, having covered almost literally every foot of the area many times in the last 40 years….I found that my work in the Kettle Moraine Forest project was of unestimatable value. In fact, I believe it is impossible to understand the (proposed national park) without a complete knowledge of what the state has accomplished. It has established the practicality of a long narrow strip as far as outdoor recreation is concerned.”

His efforts paid off. Later that year, Mr. Tobin accompanied Zillmer for several days of inspection along the proposed route. Zillmer was capturing the interest of the National Park Service, conservationists and political leaders. Bills were introduced in Congress to create an Ice Age National Park in Wisconsin.

Yet just as creation of this new type of national park was gaining momentum, Zillmer died. The vision of the Ice Age project being a linear park and trail, similar to today’s Appalachian Trail, almost passed with him.

Later in 1961, the National Park Service (NPS) concluded that, while many of the unique glacial features of Wisconsin warranted national attention, a park hundreds of miles in length would be too difficult to administer.

Grassroots supporters, State of Wisconsin officials, and NPS staff went back to the drawing board. What they came up with was the Ice Age National Scientific Reserve, an affiliated area of the National Park System composed of nine separate units around Wisconsin. In 1964, thanks to the efforts of Congressman Henry Reuss, the Ice Age Reserve legislation was passed by Congress and signed by President Johnson.

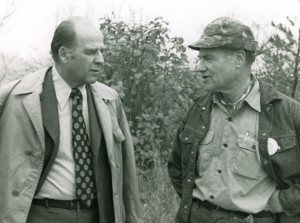

Gaylord Nelson (left) and Henry Reuss (right)

National Recognition at Last

In the early 1970s, the Ice Age Trail Council was formed to carry out Zillmer’s vision for a long-distance hiking trail. Older trails on public lands, such as the Glacial Hiking Trail in the Northern Kettle Moraine State Forest, became building blocks for the Ice Age Trail. Volunteers constructed new trail segments along much of the remaining route. Many of these new segments were built on private land after volunteers received handshake agreements with the landowners. (The Ice Age Trail Council merged with the Ice Age Park & Trail Foundation in 1990, which then changed its name to Ice Age Trail Alliance in 2009.)

Following the Trail’s first successful thru-hiker, and under the sponsorship of Congressman Henry Reuss (pictured here speaking with Gaylord Nelson [left]), the Ice Age Trail finally joined the National Trails System. On October 3, 1980, President Carter signed the law establishing the Ice Age National Scenic Trail.

Ray Zillmer’s vision seemed fulfilled.

At the Ice Age Trail Alliance we believe that if future generations are to adopt a land ethic and protect our national parks, they will need places that regularly challenge their minds to understand the natural world and engage their bodies to action.

We also believe that the Ice Age Trail is such a place, within 20 miles of 60% of Wisconsin residents and an easy drive from Chicago and the Twin Cities.

Hundreds of volunteers contribute tens of thousands of hours every year to the Ice Age Trail. Their efforts have spanned decades. Their legacy is forever.